The creation of Citizen Kane is a story of many contrasts: it is a celebration of artistic vision and a disturbing account of corporate conspiracy. It is a drama that played out in the make-believe world of sound-stages in Hollywood as well as the real-life boardrooms of New York City and at a mountaintop palace high above the Pacific coast. It is the public story of a private witch hunt: how a media organization that claimed “genuine democracy” as its maxim sought to strangle the First Amendment, first by trying to suppress Citizen Kane and then by attempting to destroy it.

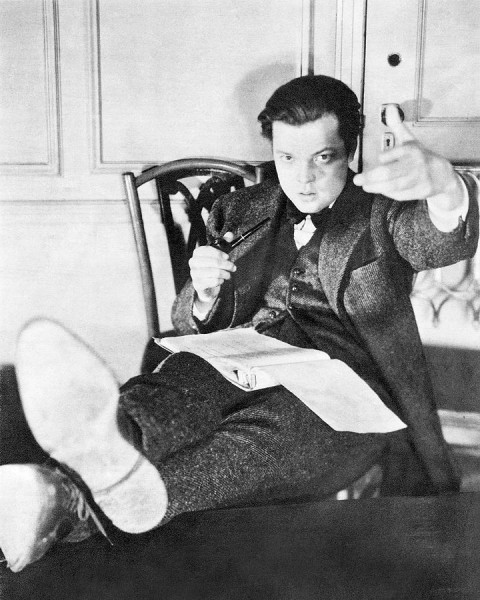

But most of all, the creation of Citizen Kane is a story that continues to amaze—and confound—those who explore how it unfolded: a twenty-five-year-old who had never worked in Hollywood created as his first production a motion picture often called the best ever made.

There is no formula for cinema excellence, but the journey to create it can be chronicled. This is the story of Orson Welles’ journey.

In 1939—the greatest year for movies among many great years—it may have seemed inconceivable that Orson Welles, then only twenty-four years old and without experience in Hollywood filmmaking, would one year later make a motion picture that would be acclaimed as the finest in screen history. Orson Welles’ arrival in Hollywood that year became another step in a career that can only be described as meteoric: it began on Broadway, expanded onto the radio airwaves, and then—literally overnight—burst into the world spotlight.

“Were Welles’ 23 years set forth in fiction form,” Time magazine reported in 1938, “any self-respecting critic would damn the story as too implausible for serious consideration.”

The often-told story of Orson Welles’ early years was indeed as improbable as one could imagine. Born in 1915 in Kenosha, Wisconsin, George Orson Welles was labeled a marvel from the moment he could speak—a youthful prodigy who has been described over the decades, with varying degrees of accuracy, as being able to read at two, discuss world affairs at three, and write plays before he was nine.

“The word ‘genius’ was whispered into my ear at an early age, the first thing I ever heard while I was still mewling in my crib,” said Orson Welles. “So it never occurred to me that I wasn’t until middle age.”

Welles’ rapid progress was so impressive that it became an endless source of jokes, even among those closest to him. When in 1940, publicist Herbert Drake asked Dr. Maurice Bernstein, Orson Welles’ onetime guardian and surrogate father, for details about his former ward’s childhood, Bernstein replied that little Orson “arrived in Kenosha on the 6th of May 1915. On the 7th of May 1915 he spoke his first words.… He said, ‘I am a genius.’ On May 15th he seduced his first woman.”

Recognizing the many exceptional qualities in their son, Richard and Beatrice Welles provided him with a near bohemian upbringing filled with art, music, literature, travel, and theater. But his parents separated when Welles was four, and his father was an alcoholic. Young Orson’s unconventional lifestyle—which became still more independent after Welles’ mother died when he was nine years old, his father when he was fifteen—instilled in him an uncanny ability for creative expression early in his life.

As a teenager, Orson Welles had the stage presence and free-spirited personality of an actor far beyond his years. While attending camp as a ten-year-old, Orson Welles produced a stage adaptation of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Later, at the Todd School in Woodstock, Illinois (the one structured educational influence of Orson Welles’ life), he starred and directed in some thirty school plays—all before his sixteenth birthday.

His was not a perfect pathway to adulthood, however. With a lifestyle of his own choosing and without parents for guidance, young Orson was indulged by others without boundaries. He saw the unlimited possibilities in life but had no checks on his creative and personal appetites.

“In some ways,” said Roger Hill, another father figure in Orson Welles’ life, “he was never really a young boy.”

Still a teenager, Orson Welles traveled to Ireland to paint, but when his money dwindled, he visited Dublin and tried to convince Hilton Edwards and Micheál MacLiammóir, cofounders of the renowned Gate Theatre, that he was not a young vagabond but actually an experienced Broadway actor. (“I don’t know what possessed me to tell that whopper,” Orson Welles later admitted.) Neither Edwards nor MacLiammóir was duped, but they both recognized Orson Welles’ potential.

“I saw this brilliant creature of 16 telling us he was 19 and had lots of experience; it was obvious to us he had none at all,” said MacLiammóir. “But he was more than brilliant, and we said, ‘We simply must use that boy.’”

Orson Welles was cast in Gate productions, in his first role (top billed at sixteen) as a nobleman in the stage version of Lion Feuchtwanger’s Jew Süss. Orson Welles then performed roles in Hamlet, Death Takes a Holiday, and more productions at the Gate and other theaters in Dublin before moving on to further adventures. (Two years later, Orson Welles would himself direct Edwards and MacLiammóir in summer stock productions in Illinois.)

When Orson Welles returned to the United States, he put his natural charm and commanding physical presence to good use. Orson Welles advanced quickly: in July 1934, he was at the Todd School, producing local plays; five months later, he was appearing on Broadway. Still in his teens, Orson Welles was becoming a sought-after theatrical performer.

But even in his early years, acting was not enough to satisfy Orson Welles’ unique creative yearnings, and he leveraged success as an actor into opportunities as a director. In 1934, he was noticed by producer John Houseman, who signed the nineteen-year-old to appear in his Phoenix Theatre production of Panic. The play survived only three performances, but the Houseman-Welles relationship continued in an alliance that was as professionally dynamic as it was emotionally explosive. On one day Houseman and Orson Welles would be praising each other and exchanging effusive messages, while on the next they would be embroiled in explosive arguments—including, later, one very public display in Hollywood that involved flaming projectiles.

In spite of their frequent personality clashes, Orson Welles-the-director and Houseman-the-producer mounted vivid theatrical productions. In 1936, for the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Theatre Project (a New Deal–era program created to provide jobs for idle actors and production staff), Orson Welles and Houseman staged, among other plays, a version of Macbeth with an all-black cast in a stunning Haitian voodoo setting. The production was so enthusiastically received that it broke all records for the presentation of the play in New York City by a single company of actors. Orson Welles, not quite twenty-one, was a sensation.

In 1937, Orson Welles and Houseman took the bold step of forming their own repertory company, calling it Mercury Theatre. It was a vibrant enterprise, with plans to mount innovative productions of classical drama. Mercury Theatre had its own “Declaration of Principles,” a statement vowing that the company would cater to patrons “on a voyage of discovery in the theater” who wanted to see “classical plays excitingly produced.”

On a scant budget, Mercury Theatre produced several of the most inventive productions ever seen on Broadway. Mercury’s first production in the fall of 1937, a staging of Julius Caesar in modern dress and with a script shortened by Orson Welles, was an artistic success and a visual triumph: Orson Welles—only twenty-two—directed and appeared as Brutus, with the play performed on a stark platformed stage painted red, while the actors wore dark business suits or Fascist-style military uniforms dyed dark green.

“The Mercury Theatre which John Houseman and Orson Welles have founded with Julius Caesar has taken the town by the ears,” said Brooks Atkinson, drama critic for The New York Times. “Of all the young enterprises that are stirring here and there, this is the most dynamic and the most likely to have an enduring influence on the theater.”

Soon after Julius Caesar came The Shoemaker’s Holiday and The Cradle Will Rock—two more hits that crowned Mercury’s success. Each Mercury play, and Welles’ other projects, found him running the show in a twenty-hour-a-day creative whirlwind of writing, editing, and directing—ever disorganized and demanding, and immensely creative.

“What amazed and awed me in Orson was his astounding and, apparently, innate dramatic instinct,” said Houseman. “Listening to him, day after day, with rising fascination, I had the sense of hearing a man initiated, at birth, into the most secret rites of a mystery—of which he felt himself, at all times, the rightful and undisputed master.”

By age twenty-three Orson Welles had conquered New York theater, but it was his work in radio that brought him to the attention of most of the public. Orson Welles had a rich compelling voice that critic Alexander Woollcott described as “effortless magnificence.” While developing his stage projects, Orson Welles also performed in hundreds of radio programs. He soon became a broadcasting star, using both his natural voice and dozens of accents and affectations for character performances (Orson Welles recalled such a frantic performance schedule that he hired an ambulance to transport him from network to network). Of his radio roles, Orson Welles is perhaps best remembered as Lamont Cranston, the mysterious crime fighter better known as “The Shadow.” In a national poll conducted by the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain, Orson Welles was chosen as the nation’s favorite radio personality of 1938.

The media found Orson Welles’ combination of talent, stardom, and youth irresistible. By then he had already been featured on the cover of Time magazine: the photo on the front of the May 9, 1938, issue showed Orson Welles, unrecognizable in old-age makeup for his role as the grizzled Captain Shotover in George Bernard Shaw’s Heartbreak House. To Time, Orson Welles was simply “Marvelous Boy.”

With Orson Welles established as a radio star, he and Houseman expanded Mercury Theatre into broadcasting. In the summer of 1938, Orson Welles and Houseman created Mercury Theatre on the Air and produced a series of entertaining but low-rated weekly radio broadcasts.

It was the Mercury program that aired October 30, 1938—a seemingly routine adaptation of a science-fiction story—that elevated Orson Welles to international celebrity status. Low rated though Mercury Theatre on the Air may have been, and despite commercial breaks and announcements that stated the program was fiction, the production of H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds convinced millions of Americans that Martians had landed in Grover’s Mill, New Jersey, and were massacring the human race.

“Radio wasn’t just a noise in somebody’s pocket—it was the voice of authority,” Orson Welles said. “Too much so—at least, I thought so. I figured it was time to take the mickey out of some of that authority.”

What began as a routine radio broadcast soon stimulated a national panic. With the attention of a nervous world fixed on the escalating international tensions that would touch off World War II ten months later, it is not difficult to understand why so many people believed that the world was being destroyed.

But the real catalyst for the terror was the timing: millions of listeners tuned in to The War of the Worlds during commercials on other programs and did not hear the disclaimers. Instead, at that moment what they first heard was the quite realistic “news broadcast” of a reporter describing the opening of an alien spacecraft. Some studies estimated that thousands who changed stations to Mercury Theatre on the Air abandoned their homes in panic without listening long enough to hear the commercials and program announcements.

By the time Orson Welles broke in late in the broadcast with his own urgent disclaimer (“This is Orson Welles, ladies and gentlemen, out of character to assure you that The War of the Worlds has no further significance than as the holiday offering it was intended to be”), it was too late. Orson Welles—who sought only to air a Halloween stunt—was stunned by the real-life hysteria and the resulting international front-page news inspired by The War of the Worlds.

“The first inkling we had of all this while the broadcast was still on was when the control room started to fill up with policemen,” Orson Welles said. “The cops looked bewildered—they didn’t know how you could arrest a radio program—so we just carried on.”

Did Orson Welles know in advance he would spark a nationwide scandal with his broadcast of The War of the Worlds? No one, not even an artist with an imagination as vivid as Orson Welles’, could have envisioned the combination of dramatic content and on-air timing that was needed to terrify millions. But once it was done, Orson Welles certainly capitalized on the opportunity.

At a press conference the morning after the broadcast, Orson Welles was as sincere as a choirboy, answering questions with a furrowed brow, the gentlest of tones, and shocked surprise at what had occurred the night before. Orson Welles, a commentator said much later, “was masterful in his astonishment.” Orson Welles repeated over and over again how “deeply regretful” he was. However, he also carefully expressed his surprise that a radio drama could convince millions that the end of the world had come.

“It would seem to me unlikely that the idea of an invasion from Mars would find ready acceptance,” Orson Welles told reporters. “It was our thought that people might be bored or annoyed at hearing a tale so improbable.”

(Three years later, Orson Welles would send a less-than-subtle message in his first words during the newsreel in Citizen Kane: seen as an old man being interviewed on his return from Europe, Kane says, “Don’t believe everything you hear on the radio.”)

By the next day, Halloween 1938, the international spotlight shined on Orson Welles.

“At the moment he was shocked and dismayed, but he was also aware that suddenly his name was on the front page of every newspaper all over the world,” said daughter Chris Welles Feder sixty years later. “Overnight, he had become internationally famous as a result of this broadcast. I don’t think he was sorry about that.”

And famous he was. After The War of the Worlds, Orson Welles was no longer solely a radio and Broadway star: the attention of the country was, for the moment, focused on this mildly amused twenty-three-year-old, whose Halloween prank had made him a sensation. Orson Welles would continue to work in theater and radio, but Hollywood was already beckoning.

HARLAN LEBO is the author of CITIZEN KANE: A Filmmaker’s Journey a senior fellow at the Center for the Digital Future in the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. Lebo has written books about The Godfather, Casablanca, and a coffee-table photo book on Citizen Kane, and served as a historical consultant to Paramount Pictures for the fiftieth anniversary of the theatrical release of Citizen Kane. He lives in California.